In our first blog of the new academic year we explored the importance of prevention over cure and the role of preparation in reducing the risk of injury in youth sport. We suggested that the new school year presents an abundance of opportunities for sports pupils to engage in sport at full throttle. However, we highlighted the need for a holistic perspective on preparation for the up and coming demands of multiple training sessions and fixtures off the back of an extended holiday period. We compared this approach to the investment in preparing for school exams through a thorough revision schedule and may be even the experience gained through mock exams (friendly matches). Those pupils with a passion and ability across multiple sport will also find their schedules dense with time allocated to various training sessions and competition across a range of sports. So, how do we go about scheduling for multiple sports with the pupils we support? How do we go about optimising the potential of capable mulitsporters? What’s our approach to discovering brilliance across a variety of sports?

The evidence is compelling that a multisport experience in youth sport is good and healthy for both personal and physical development and has been shown to be advantageous in supporting the minority of people that have made it to the very highest levels of sport. However, whilst the research literature is extensive on the risks and proposed guidelines around sports specialisation, there is a paucity of evidence to help support and guide the development of applied multisport programmes in youth sport.

As the saying goes, ‘balance is not something you find, it is something you create’. In light of this, we have gone on the front foot and looked to bring to life a principle led approach to supporting the balanced and timely development of multisport pupils. In short, we have created our approach to discovering brilliance in this demographic. This approach has been focused around 4 principles:

1. Generate a longer term perspective – by framing discussions with pupils, parents, coaches and teachers we are able to project 6-12 months ahead and consider how the current ‘multisport mix’ supports the pupils development moving forwards

2. Each case viewed through a wide lens – we must work collaboratively to contextualise pupil load across academic, pastoral and co-curricular domains

3. Pupil centred – any option that is developed must be for the best of the pupil across all domains

4. Generating multiple solutions – within the ‘multisport mix’ a number of options need to be presented to stakeholders for discussion with the pupil full involved

Our experiences to date suggest that these principles have helped focus all parties on what’s best for the pupil now and for the future. They have helped drive an approach in which the ‘multisport mix’ is possible and productive. With the integration of valid guidelines drawn from the sports specialisation literature, such as total hours of organised sport per week should be less than the pupil’s age in years, a holistic development approach around our capable multisport pupils is now in action. What’s your approach to discovering brilliance across a variety of sports?

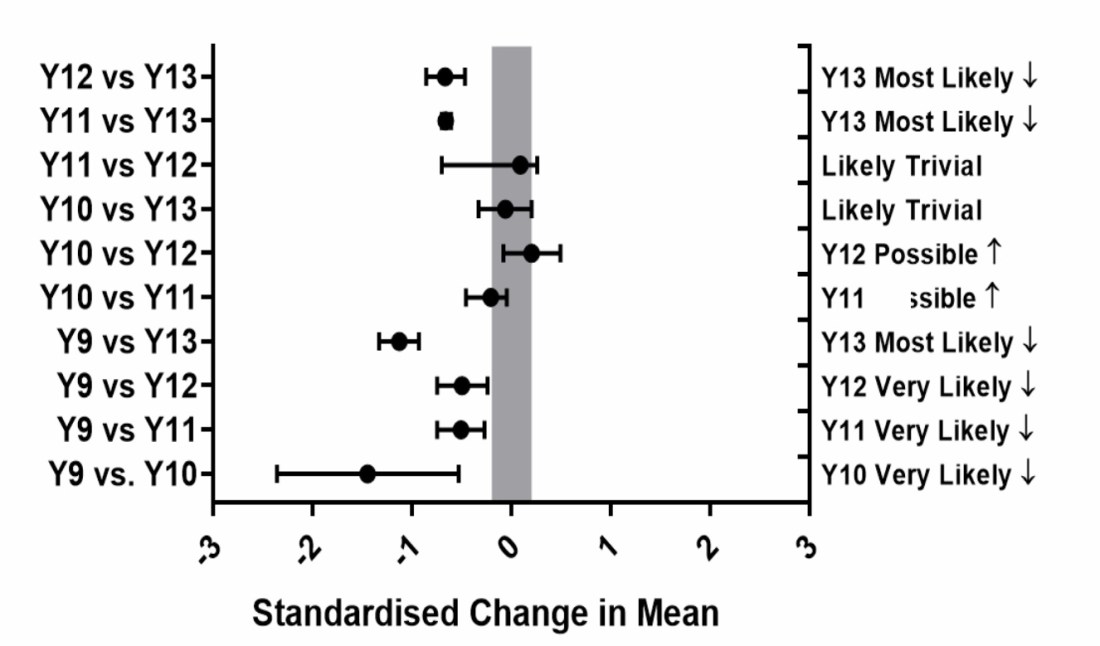

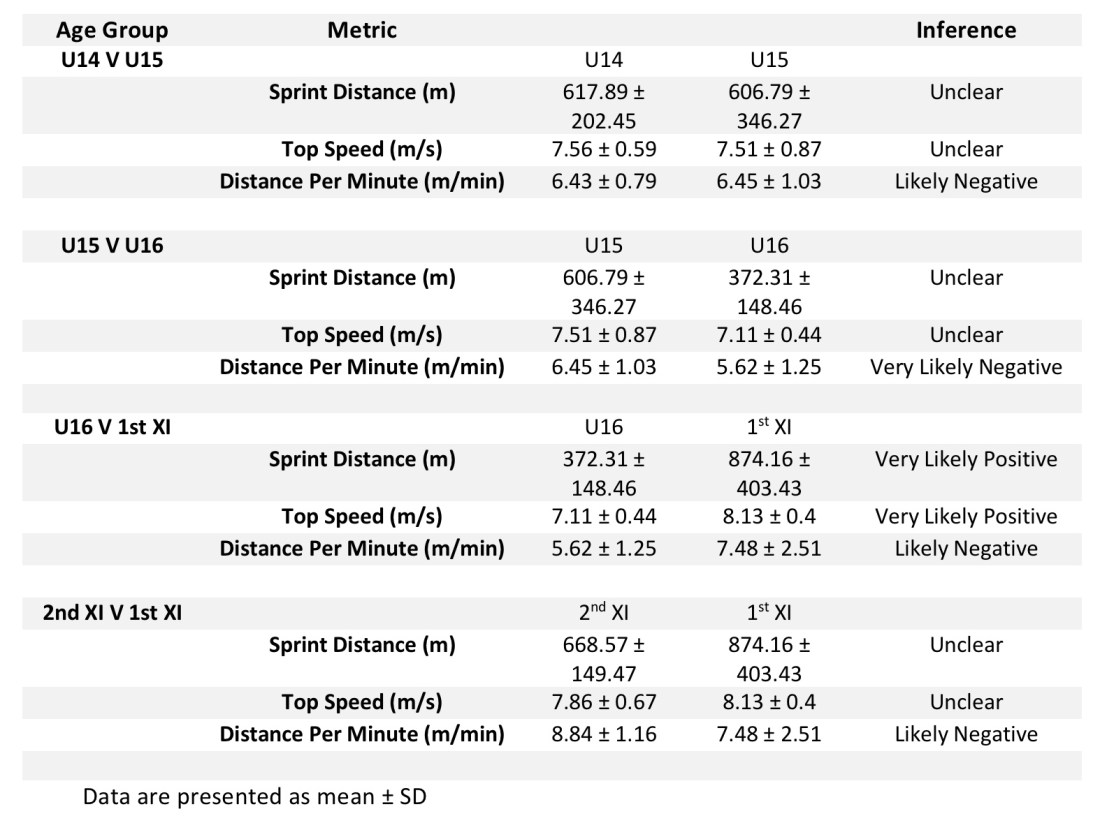

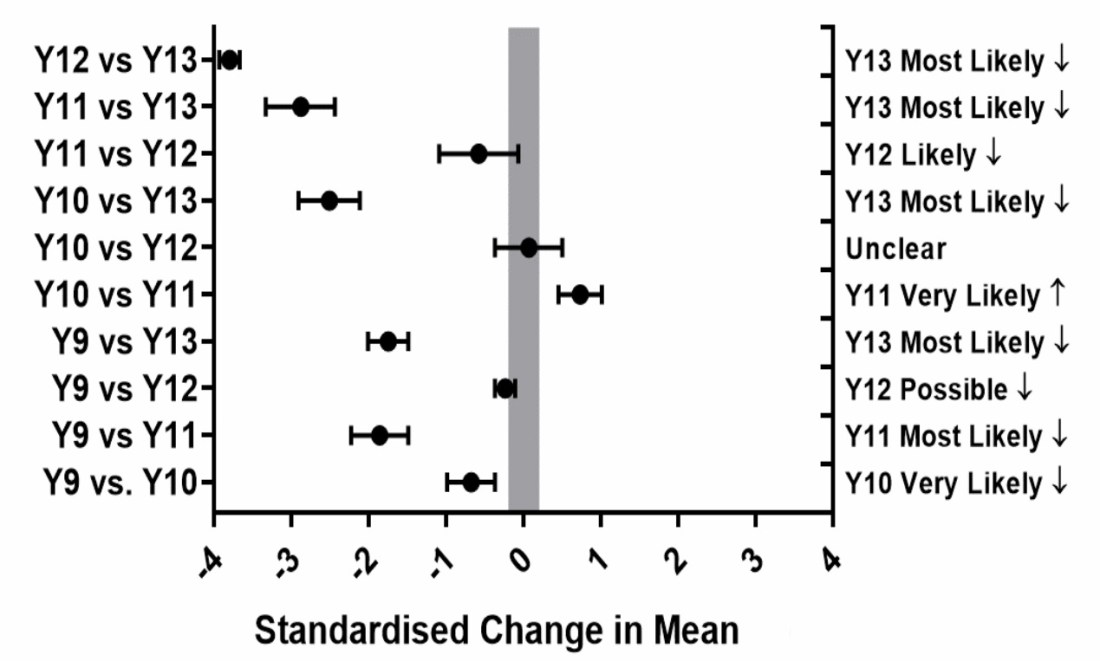

Figure 1. Consecutive year group differences in 5m sprint performance. Data represented as standardised change in mean (± 90% CI) with MBI’s.

Figure 1. Consecutive year group differences in 5m sprint performance. Data represented as standardised change in mean (± 90% CI) with MBI’s.